Gustavus Adolphus: Lion of the North

By Isaac Blatter

Oddly, the fall of the brilliant King Gustavus Adolphus on the field of battle marked both the beginning of Sweden’s rise to power and the end of one of the most aggressive ages of military reform. This period, roughly the beginning of the 1600s, saw the shift from hand-to-hand medieval combat to the musket-armed regular armies of the 18th century. The Duke of Alba began the change to musket firepower; Maurice of Nassau continued the trend, organizing the new weapons more effectively. But it was Gustavus Adolphus who was to have the most profound impact on this revolutionary change in weaponry and tactics.

The Duke of Alba, who led the Spanish forces reconquering the Netherlands, was one of the first to realize the importance of musketeers in an army increasingly dominated by infantry. Alba began his changes with the tercio, the Spanish infantry regiment originally composed of a square of pikes. In 1571 he added two companies of shot to the fringes of the square, making the shot-to-pike ratio 2:5; by 1601 the ratio had increased to 3:1.

Maurice of Nassau, son of the original William of Orange, took the next step in the military reformation begun by Alba, his father’s mortal enemy. He developed the musket line in which by both standing 10 deep and alternating ranks an army could pour continuous fire into enemy formations. This tactic required precision that could only be obtained through constant drill. Parade- ground discipline became an integral part of his army’s regular exercise. Maurice’s brother, John of Nassau-Siegen, built the first military academy (at his capital of Siegen in western Germany) and produced the first drill book to teach the discipline needed for the increasingly complex maneuvers that the new tactics demanded.

Crowned King at 17

When Gustavus Adolphus ascended the Swedish throne in 1611 at the age of 17, his army consisted of recalcitrant nobles and peasant levies who refused to fight outside the borders or to wield weapons they didn’t like, such as the pike, which had made obsolete the heavy cavalry of the Middle Ages. At the battle of Kirkholm early in Gustav’s reign, Polish cavalry annihilated his raw army, killing three times their own number.

Gustav set about to remedy the situation, much like Peter the Great in Russia would half a century later. Both of these monarchs took a hands-on approach. Both were expert in most of the disciplines they reformed and could hold their own with their officers and men. Gustav was an excellent artillerist, siege engineer, sea captain, and drillmaster.

Perhaps the most important of Gustav’s reforms was the Ordinance of Military Personnel, issued in 1620, which required each province to organize its men into “files” of 10 men each, from which the military would draft a specified number. These men were then organized into provincial regiments consisting of six squadrons of 408 men each, plus officers.

Gustav drilled his men in much the same way Maurice did, but he emphasized the practical over the parade-ground exercises. A second improvement was a quickening of the musketeers’ reload time. Paper cartridges and the use of Wheelock muskets in place of the cheaper but less reliable Matchlock muskets reduced the period of the musketeers’ reloading. Because of the faster recharging interval, Gustav was able to shrink his ranks to six deep—three by the battle of Lutzen—allowing his army to cover a much wider front. This gave him greater potential for enveloping his enemy’s flank, and the ability to move quickly and efficiently, a capability that would prove decisive at the battle of Breitenfeld.

Gustav’s increased firepower was further improved by the addition of artillery support. He standardized the artillery into 6-, 12- and 24-pounders. He also designed a 3-pounder—his regimental piece. This 3-pounder infantry-support gun was an important improvement on traditional artillery. It could fire once every three minutes, because of a cartridge wired to the ball. It could be transported by one horse, or two to three men, and was ideal for regimental support. Each regiment received four of these light, infantry-support guns.

But Gustav’s most revolutionary change was his combination of all of these elements into a mobile and reactive unit. The pike hedge that every army employed was a formidable defensive weapon, especially against cavalry charges. But Gustav had learned from the Poles and knew the potential of the cavalry’s horse/man combination. His cavalry departed from the contemporary caracole tactic, by which the cavalry trotted up to the enemy line, discharged their pistols into the pike hedge, and rode off to reload. Gustav equipped his cavalry with swords and expected his men to use them. Detachments of musketeers would follow the cavalry, along with the horse artillery 3-pounders.

One Long and Continued Crack of Thunder

Although these detachments slowed the cavalry, they provided necessary support to punch holes in the enemy pike hedge. The musketeers and artillery would fire a single—according to a contemporary Swede—thunderous volley, in order to “pour as much lead into your enemy’s bosom at one time … and thereby you do them more mischief … for one long and continuated crack of thunder is more terrible and dreadful to mortals than ten interrupted and several ones.” Then the cavalry would charge into the reeling pike hedge, causing chaos throughout the enemy’s line.

Previously pike formations such as the tercio had been primarily defensive in nature. This is apparent in the shape of the formation, which had musketeers at the corners, distinctly reflecting the shape of the era’s fortresses. Neither this formation nor Maurice’s cumbersome lines were well suited to movement. Gustav did not abandon the pike; rather he made it one of his prime offensive weapons. He used them in much the same way as cavalry—musketeers and artillery punched holes in the enemy lines, and the pikes followed through with a charge.

Gustav earned a seat on Napoleon’s list of the six or seven greatest commanders of all time for another reason: He sought battle. At the time, most commanders were not willing to risk the uncertainty of large-scale combat, especially because the bulk of most armies were composed of mercenaries.

Pay-for-hire soldiers had become the solution to the military problems of the Middle Ages, and by the time of Gustav’s reign, they were still the most important source of troops for rulers. The peasant levies of the Middle Ages did not make the best soldiers, and their lack of discipline could endanger a kingdom. Standing armies were, however, much too expensive for the relatively weak central governments of the Middle Ages. Thus bands of mercenaries came to predominate, most notably Swiss and later Scottish bands. These were professionals, disciplined, and well trained in their art. They were, however, unreliable, often defecting to the winning side, and sometimes even refusing to obey orders.

An Army of 150,000 Mercenaries and Conscripts

Instead of tolerating problems as did other leaders, Gustav took the first step toward solving them. His reforms set the standard for conscription and the national conscript armies that would dominate Europe for the next century and a half. Even in Gustav’s Swedish Army, however, a large percentage of the troops were mercenaries. This was common at the time, and of the 36,000 men that landed with him at Usedom in 1630, about half were soldiers of fortune. This proportion continued to increase: In 1631 three-fourths were hirelings and in 1632 approximately nine-tenths of his 150,000-man force were so. Nevertheless, there always remained an important native Swedish corps around which his army was formed. Gustav’s 1621 Articles of War set a high standard of discipline for both his regular conscript soldiers and his soldiers of fortune. But the most important reason he was able to control his mercenaries was the fact that he won.

The Thirty Years War and German soil became the trial grounds for Gustav’s new army. Gustav let Protestant Swedes support their religious cause in Germany for fear of Catholic Habsburg hegemony. On July 6, 1630, the Swedish Army of 36,000 debarked at Usedom in Pomerania.

Gustav spent most of a year unsuccessfully negotiating with the various German electors for permission to pass through their territories. Then on May 20, 1631, Count Tilly, the imperialist Habsburg general, sacked the Protestant city of Magdeburg, which broke out in flames; about 20,000 civilians perished. The Protestant electors delayed no longer, setting their energies and resources behind Gustav. So when Leipzig was besieged, Gustav, with the aid of the elector of Saxony, marched to relieve the beleaguered city.

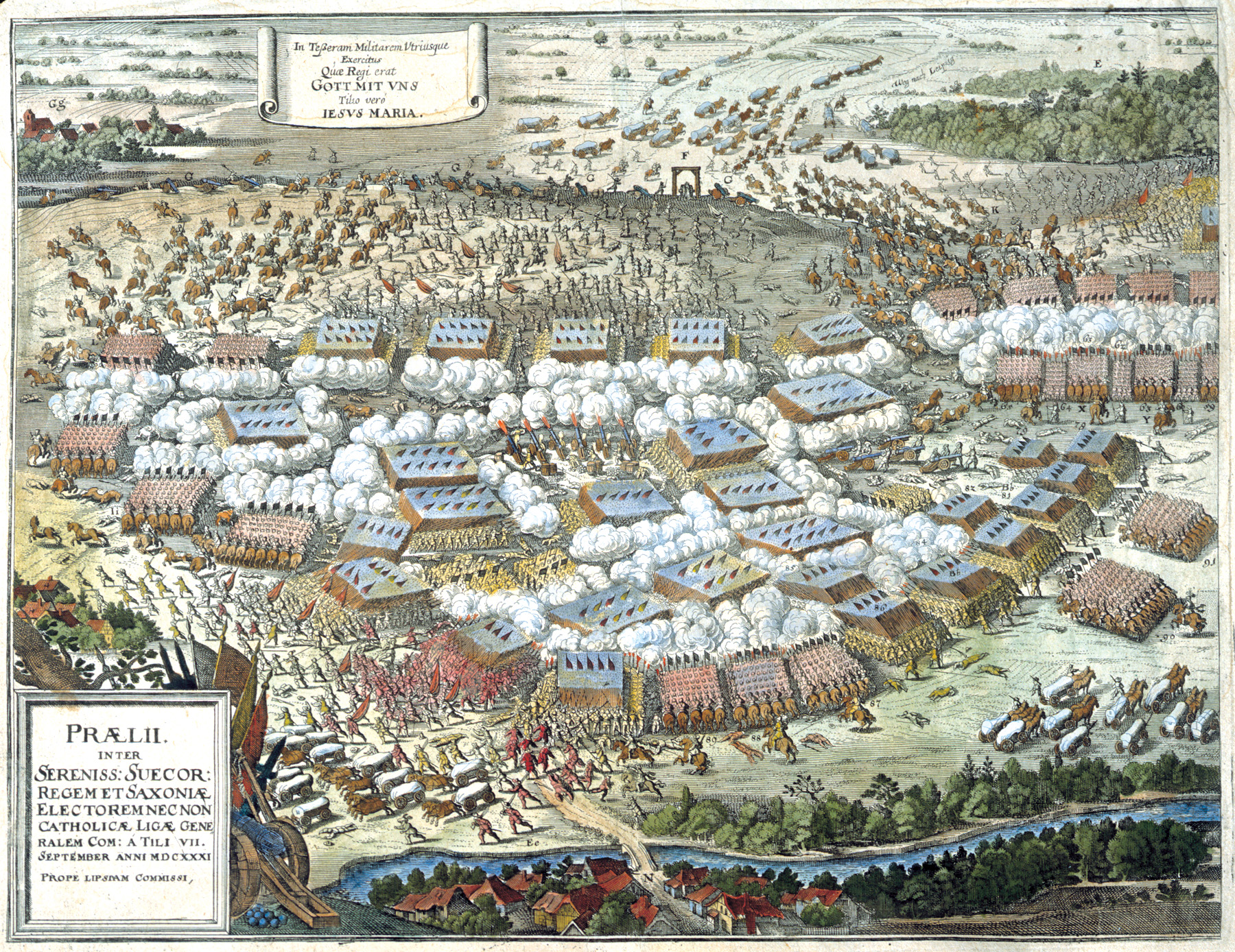

Gustav and Tilly met on September 17 near Breitenfeld, a town outside Leipzig, and fought what became Gustav’s most famous battle.

Tilly took the field with 21,400 foot and 10,000 horse, while Gustav mustered a total of 28,000 foot supported by 13,000 horse. The battle began with a three-hour artillery duel, in which Gustav’s standardized and plentiful artillery battered the relatively few Habsburg pieces. The Habsburg cavalry, stressed by the continuous bombardment, broke ranks and charged. The Swedes’ right repulsed them, but the cavalry on the Habsburg right flank charged the Swedes’ Saxon allies, who turned and fled even before the enemy had closed. This offset the discrepancy in numbers and left only the Swedes still holding the field against Tilly’s army.

Gustav’s superior training, tactics, and organization now paid off. He was able to quickly change fronts, shifting his cavalry and his infantry reserves to his unprotected flank. The tercio formations of the enemy were slow to respond to the opening, while Gustav’s more mobile troops, supported by disciplined artillery, were able to pour fire into the cumbersome Habsburg formations as they maneuvered.

The Lion of the North

The Swedish king then charged from the right at the head of his cavalry, capturing the Habsburg guns and turning them on their owners. The imperial troops fought desperately, but the relentless firepower of the Swedes devastated them, and in the ensuing fight the imperialists were routed. The Habsburg army under Count Tilly suffered 8,000 killed or wounded, and an additional 9,000 either deserted or were captured. The Swedes lost fewer than 3,000 men, and captured all of the imperial guns plus 20 regimental banners. Tilly was stunned and moped about in inaction while Gustav, now known as “The Lion of the North,” conquered most of Germany.

The Battle of Breitenfeld was the epitome of Gustavus Adolphus’s style and the proving ground for his revolutionary reforms. It heralded the coming of 18th-century tactics, and the sole use of the gun in combat.

At another of Gustav’s victories, the famous crossing of the Lech River, Count Tilly was mortally wounded. Gustav went on to conquer most of Germany before meeting Tilly’s replacement, Count Wallenstein, on the battlefield of Lutzen in 1632. There Gustav died at the head of a charge. The battle was won, but the war went on for another 16 years. Under the leadership of Cardinal Richelieu and fearing Habsburg hegemony, Catholic France entered the war on the Protestant side. This tipped the balance of the war in favor of Sweden and her allies, devastating Germany in the process.

Even the best army in the world cannot win in the hands of an incompetent general, and this Gustav was not. Many of the earlier reformers, Maurice of Nassau foremost, were not able either to enact their reforms or use them effectively in battle, but Gustav accomplished both.

The lessons learned by Gustav’s short but brilliant career have not been lost on history. His ability to combine new weapons with innovative tactical methods and to apply them successfully on the battlefield placed him on Napoleon’s list of the top generals. His ability to effectively combine improved firepower and mobility was his greatest attribute, and has been an important factor in the success of generals such as Rommel and units such as the first Air Cavalry.

Back to the issue this appears in

Link nội dung: https://tcquoctesaigon.edu.vn/gustavus-adolphus-a68419.html